Round 176 Theme Poll

Pick the next theme of fancake:

Books & Writing

3 (42.9%)

Protest & Revolt

2 (28.6%)

Working Together

2 (28.6%)

Pick the next theme of fancake:

Books & Writing

3 (42.9%)

Protest & Revolt

2 (28.6%)

Working Together

2 (28.6%)

Submitted by Charles Belov:

I've been browsing through the proposed Unicode 17 changes, currently undergoing a comment period, with interest. While I don't have the knowledge to intelligently comment on the proposals, it's good to see that they are actively improving language access.

I'm puzzled that some new characters have been added to the existing Unicode CJK Unified Ideographs Extension C (6 characters) and Unicode CJK Unified Ideographs Extension E (12 characters) rather than added to a new extension. But the most interesting is the apparently brand-new Unicode CJK Unified Ideographs Extension J, with over 4,000 added characters.

I found the following characters of special interest:

– 323B0 looks like the character 五 with the bottom stroke missing.

– 323B3 looks like an arrangement of three 三s – does it possibly mean the same as 九?

– 32501, while not up to the character for biang for complexity, is nevertheless quite a stroke pile: the 厂 radical enclosing a 3 by 3 array of the character 有

– 3261E is the character 乙 in a circle, which doesn't look quite right to me as a legit Chinese character

– 326FB seems sexist to me: three 男 over one 女

– 33143, similarly to 32501, has ⻌ enclosing a 3 by 3 array of the character 日

Alas, macOS does not yet support the biang character, so I can't include it in this email. Hopefully someday.

Character additions

VHM:

Note that, as it has been since the beginning of Unicode, CJK gobbles up the vast majority of all code points (see Mair and Liu 1991).

What is this fact telling us about the Chinese writing system, particularly in comparison with other writing systems? How does one account for this disparity? What is the meaning of this gross disparity?

The average number of strokes in a Chinese character is roughly 12.

The average number of strokes in a letter of the English alphabet is 1.9.

The average number of syllables in an English word is 1.66 (and 5 letters).

The average number of syllables in a Chinese word is roughly 2 (and 24 strokes).

The average number of words in an English sentence is 15-20.

The average number of words in a Chinese sentence is 25 (ballpark figure; see here)

Chinese has more than 100,000 characters.

English has 26 letters.

Total number of English words; over 600,000 (Oxford English Dictionary)

Total number of Chinese words: a little over 370,000 (Hànyǔ dà cídiǎn 漢語大詞典 [Unabridged dictionary of Sinitic])

und so weiter

Selected readings

Which 2001 Clarke Award Finalists Have You Read?

Perdido Street Station by China Miéville

17 (65.4%)

Ash: A Secret History by Mary Gentle

13 (50.0%)

Cosmonaut Keep by Ken MacLeod

8 (30.8%)

Parable of the Talents by Octavia E. Butler

10 (38.5%)

Revelation Space by Alastair Reynolds

9 (34.6%)

Salt by Adam Roberts

4 (15.4%)

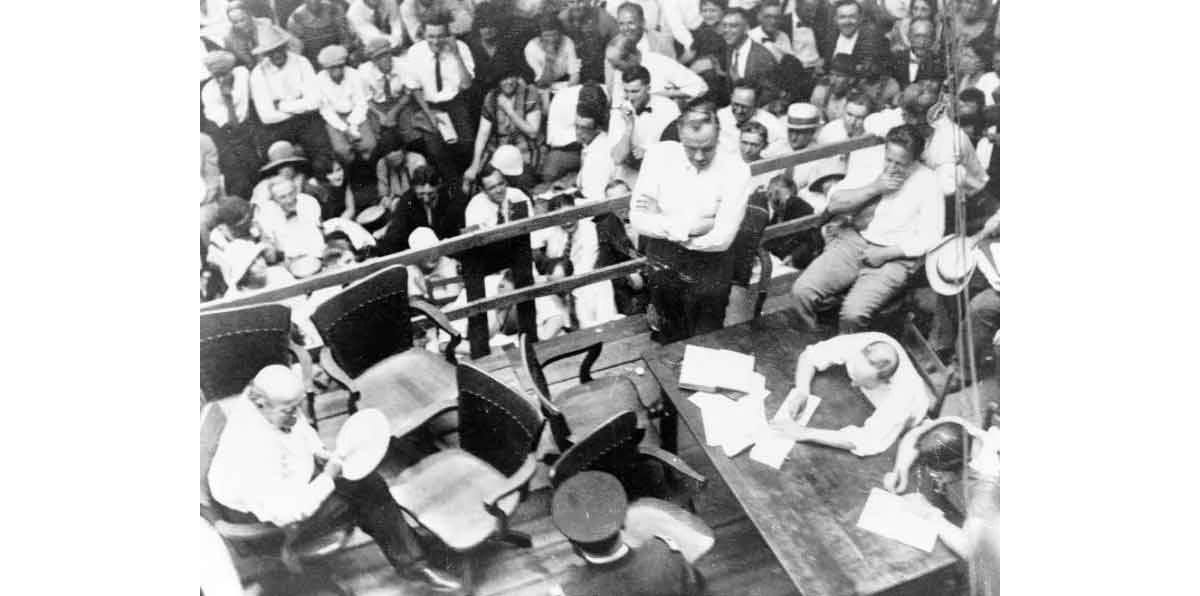

Next month I’ll be heading to Dayton, Tennessee, for the centennial of the “Trial of the Century”, the case of Tennessee v. Scopes. The good people of Dayton and the Rhea County Historical Society are putting on a weeklong series of events to commemorate the trial, described at the Scopes100 site. As part of the events, they’ve invited me to come and share the current picture of human evolutionary science. On July 16 and 17 I’ll be part of a symposium taking place in the historic Scopes Trial Courtroom.

I’m really looking forward to this event. With the rapid changes in the science of human origins, I’ve got a lot to talk about!

The Scopes Trial defined a turning point in the social history of evolutionary science. It was the first of many flareups of conflict among people of faith, school boards and legislatures, scientists and educators. With this history of conflict, many of my colleagues in anthropology and biology see a rigid antagonism between scientific approaches to humanity’s history and religious traditions.

I don’t really share that point of view.

I enjoy talking with people of all denominations and backgrounds to share what I have seen as a scientist. The fossil, genetic, and archeological evidence are so strong. Most people just don’t know how much evidence there really is. What I’ve found is that people are always fascinated at the discoveries, and big discoveries are unfolding at a faster rate today than ever before.

Over the next month I’ll be preparing for the centennial. There are some great sources on this topic, including the Pulitzer Prize-winning book Summer for the Gods by Edward Larson. I’ll be reflecting on some parts of the history that stand out to me from today’s point of view, and also thinking about were the science of human origins has come, and where it’s going.

In this post, I’ll look at the background of the trial.

The anti-evolution movement in the U.S. did not emerge naturally from religion of the late nineteenth century. It was built by design.

When Charles Darwin first published his work—the Origin of Species in 1859, followed by Descent of Man in 1871—he did indeed rouse antipathy and resistance from many religious leaders both in Europe and North America. The famous public debate between Thomas Huxley and Bishop Samuel Wilberforce in 1860 was the best known example of disquiet that was very widespread.

A mere generation later, by the 1880s, attitudes among scientists and many people who were prominent in society—including religious leaders—had transformed toward acceptance and accommodation of evolution.

On the scientific side, zoologists, botanists, and natural historians found evolution to be an enormously productive way to look at their subjects. The evidence of common descent of species is and was overwhelming.

Even so, not all were convinced about Darwin’s idea of natural selection. Many thought this too weak and too slow. Some favored an older explanation, Lamarckian inheritance, as the most important mechanism for evolution—one that Darwin himself thought likely to apply in some cases. This led some scientists to distinguish the idea of evolution from the specific mechanism of natural selection, which they called Darwinism.

On the societal side, academics, political leaders, and leaders within some religious groups saw much in Darwin’s ideas that appealed to them. The slogan “survival of the fittest”, coined by the sociologist Herbert Spencer, was emblematic of a widespread attitude about competition of people within society, which became known as “Social Darwinism”. Darwin himself had written about competition among races as part of his ideas of human evolution.

Many Christian leaders and thinkers followed these developments in science and worked to find new alignments between such modern ideas and their beliefs. They reinterpreted Bible verses and old traditions in light of natural history. This approach, shared by denominations like Episcopalians, Presbyterians, Methodists, and Catholics, by the 1900s was known as “modernism”. It kept religion relevant for many people who might otherwise have turned toward agnosticism.

But the world was changing, nowhere faster than in the United States.

Through the turn of the twentieth century, millions of new immigrants arrived in America. At the same time, cities were growing and drawing migration from rural areas nationwide, especially the beginning of the Great Migration of Blacks from the rural South into northern cities. Wage work in factories was supplanting agriculture and skilled trades, challenging traditional family structures as young people moved to the cities for work. The fastest-changing social forces grew with the financial and industrial power of the cities of the Northeast. The old North versus South political divide was realigning toward an urban versus rural one, pushing people of the Great Plains and mountain West politically toward the Democratic Party.

Three massive interrelated phenomena rose in the midst of these forces: Progressivism, Fundamentalist Christianity, and William Jennings Bryan.

It was Bryan more than anyone who saw how a crusade against teaching evolution could galvanize people and pressure state legislatures on other issues. He transformed this social issue into a political cause that would span a century.

Born in Illinois, Bryan came to prominence in Nebraska politics and became the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1896, 1900, and 1908. He went down to defeat in all three elections, but his great skill in speechifying and his knack for championing issues that unified Democrats from different regions, held the strong loyalty of the party. He retained great influence in the 1912 nomination contest, which Woodrow Wilson won with Bryan’s backing. As a result, Wilson made Bryan his Secretary of State—a position that the isolationist Bryan resigned in 1915 as he saw Wilson angling toward entry into the First World War. After leaving office, Bryan set his sights on two crusades: the old cause of Prohibition, and the newer one against Darwinism.

Bryan railed against the idea of “survival of the fittest”. He saw that Social Darwinism led almost inexorably to eugenics, which was gaining enormous support in the 1910s and 1920s across the country among scientists and progressive policymakers. Bryan recognized eugenics as brutal and degrading, and opposed sterilization laws and other measures sponsored by eugenicists. For Bryan, the concept of human evolution reduced humans to the level of animals in direct contradiction to Biblical teaching.

In this, Bryan rode the wave of the newly born Fundamentalist movement. Launched from the pulpits of energetic pastors like the Minnesota Baptist William Bell Riley, Fundamentalism was an interdenominational reaction to the “modernist” doctrines of other denominations. The movement’s principles were encapsulated in a multi-author series of essays titled The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth, which commented on current social issues through literal interpretations of Bible verses.

As I began reviewing this history, it struck me how young the Fundamentalist movement was in 1925. The Fundamentals appeared between 1910 and 1915. The establishment of the World Christian Fundamentals Asssociation, launching the national coordination of churches that were part of the movement, was in 1919.

The anti-evolution crusade was not an isolated issue. Fundamentalists campaigned for policies and measures that they saw as defending families, like prohibition of alcohol and opposition to jazz music and racy movies. They saw immigration, especially from non-Protestant regions of the world, as disrupting social and moral harmony.

Up to the turn of the twentieth century, churches were the largest supporters and organizers of education. Where public schools existed, they had curricula in which the Bible and religious concepts had an honored place. High school-level education was rare; only a small fraction of boys and hardly any girls attended this level.

By turn of the twentieth century states poured more and more funding into public school systems. America was seen as a “melting pot” of immigrants from many nations, and the place tasked with assimilating immigrant children was the growing system of public schools. State legislatures invested in high schools, and attendance through the 1910s and 1920s rapidly grew. Professors from institutions like Yale and the University of Chicago wrote modern curricula and textbooks full of progressive educational theories.

In the field of biology, the modern curriculum meant evolution.

William Jennings Bryan argued that parents and local leaders, not distant professors, should determine what the public schools should teach. Acting with the WFCU, he lobbied state legislatures around the country to ban the teaching of evolution. The campaign spread across more than a dozen states, with its first victory in Oklahoma in 1923, where the law prohibited textbooks that taught Darwin’s theory.

In Tennessee, the anti-evolution legislation was known as the Butler Act, for its sponsor John Washington Butler. Butler worried that children would reject Biblical teaching about creation, after learning about human evolution in schools. The act specifically singled out human evolution as forbidden within classrooms of the state. The act was signed into law by Tennessee Governor Austin Peay on March 21, 1925.

“It shall be unlawful for any teacher in any of the universities, normals, and all other public schools of the State ... to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.”—Butler Act, passed in 1925

Bryan had privately urged against including penalties in the law. People had a respect for schoolteachers and he understood that prosecuting them would raise opposition to laws meant to shape and restrict curriculum. Nonetheless, the Butler Act prescribed fines up to $500 for violations.

This penalty opened the door to challenges in the court system. The new American Civil Liberties Union, itself founded in 1920, saw the freedom of inquiry imperiled by laws that would restrict discussion of subjects like evolution in classrooms. Immediately after the passage of the Butler Act, the ACLU began to run advertisements in Tennessee newspapers, offering legal representation to any teacher who wanted to challenge the new law.

With the passage of the Butler Act, the stage for the Trial of the Century was set. The clash that unfolded in Dayton, Tennessee, would pit Bryan personally against the scientific community and the most notorious trial lawyers in the country, Clarence Darrow. It would end with Bryan’s unexpected death in Dayton days after the trial’s conclusion.

“The radio audience was fortunate,” says Williams. “They were able to hear William Jennings Bryan stand up near the microphone and say that he was going to defend the Word of God against the greatest agnostic and atheist in the United States. That was compelling radio.”—American Experience

The circus that would eventually unfold, complete with trained chimpanzees and folk songs, was absolutely typical of the 1920s. Still, the degree of nationwide attention was unprecedented. I’ll get into the media coverage in my next post.

To conclude this one: I’ve taught human evolution in several parts of the United States. My long-term positions as a student, postdoc, and professor have been in Kansas, Utah, Michigan, and Wisconsin. I’ve also lectured all over the country, and have been interacting with a wide range of folks online for more than twenty years. Even so, many parts of this history were new to me.

As someone who teaches and researches human evolution, I’m asked about American creationism almost more than any other social issue. People in other countries find it puzzling why the United States has so much controversy about teaching evolution.

The emergence of Fundamentalism was tied to the anti-evolution crusade. Among the many social issues championed by pastors and others active in the movement, the fight against teaching Darwin was the most distinctive. Turning the issue into a legislative battle on a local and state level added strong solidarity, sending a message that the faithful could create change by flexing their political muscle. It helped the movement appeal to more and more believers from mainstream churches, who were often disillusioned by the more liberal thinking by their own ministers and pastors.

It’s a tension that we still see today, and that’s why evolution has remained a contentious issue in education for a century.

Notes: There has long been less acceptance of biological evolution in the U.S. than in Europe or Canada. Even so, that difference has often been exaggerated, and it is diminishing. In the most recent surveys, only 17% of Americans profess to believe that humans did not evolve from earlier forms of life.

Larson, E. J. (2008). Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America’s Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion. Hachette UK.

Levine, L. W. (1987). Defender of the Faith: William Jennings Bryan, the Last Decade, 1915-1925. Harvard University Press.

Marsden, G. M. (2022). Fundamentalism and American Culture. Oxford University Press.

Masci, D. (2019, February 6). Darwin in America. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2019/02/06/darwin-in-america-2/

Monkey Trial | American Experience | PBS. (n.d.). Retrieved June 16, 2025, from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/monkeytrial/

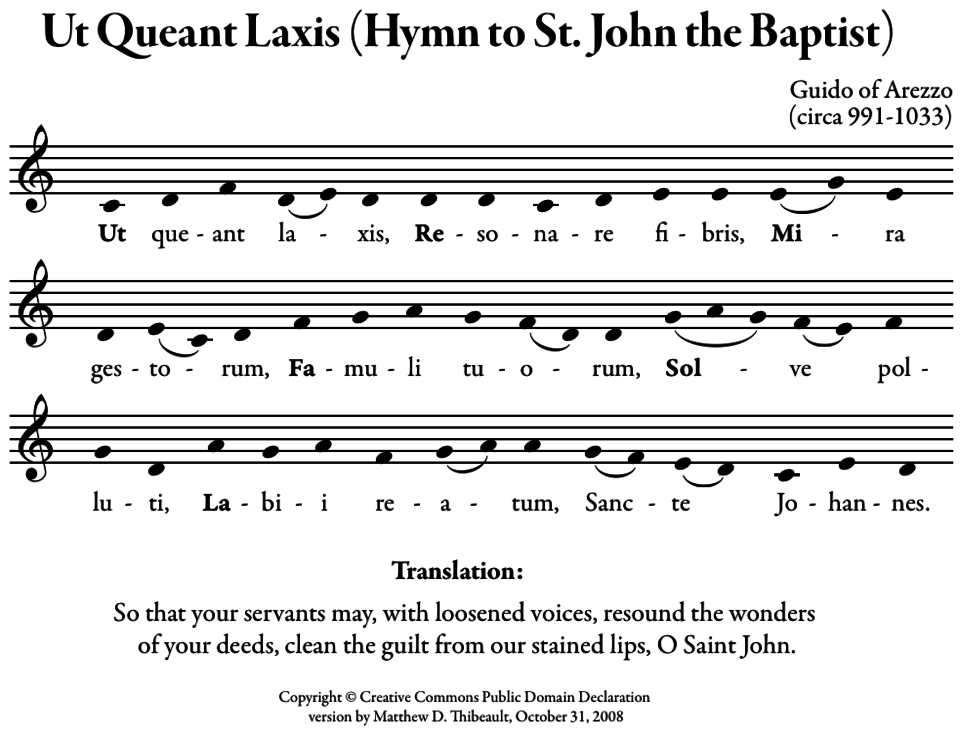

Where did the familiar syllables of solfège (do, re, mi) come from? Eleventh-century music theorist Guido of Arezzo collected the first syllable of each line in the Latin hymn “Ut queant laxis,” the “Hymn to St. John the Baptist.” Because the hymn’s lines begin on successive scale degrees, each of these initial syllables is sung with its namesake note:

Ut queant laxīs

resonāre fibrīs

Mīra gestōrum

famulī tuōrum,

Solve pollūti

labiī reātum,

Sancte Iohannēs.

Ut was changed to do in the 17th century, and the seventh note, ti, was added later to complete the scale.